#65 - Blue Screenlight is the Number 1 Sleep Myth of Our Time - Part 1

The Problem of Extrapolation

There is a common phrase in sleep science that goes something like this:

“Screens emit blue light that make it harder to fall asleep”.

As one of the first researchers to test this, I’m calling B.S. on this statement. Right next to the claim that ‘sleep training babies raises the cortisol levels”, the above statement has to be the Number 1 Sleep Myth going round.

So this blog is going to prove that to you.

But first, you have to understand the origin of this myth - which starts in the 1990s.

Evening Bright Light

Like many police officers before him, my new client had experienced trauma.

And although he had successfully decreased his trauma symptoms after enrolling in a new therapy at my university, he still had some residual insomnia. So the trauma therapist referred him to me.

By the time I saw him, he had already seen his psychiatrist - who had already begun CBT for insomnia.

But one look at his sleep diary (and his face) meant that I knew that the psychiatrist had missed something important.

This police officer’s body clock was ‘phase advanced’.

Phase advanced means that one’s body clock is timed too early. They struggle to stay awake after dinner, and wake up at 4 AM and cannot get back to sleep.

Fortunately, I had learned how to treat this condition from my mentors - Prof Leon Lack and Dr Helen Wright - both of whom discovered in the 1990s that bright light was effective at changing the timing of an early body clock …

… and then within several years, also discovered that bright blue light was really effective at delaying the body clock (which is really helpful for people like my new ‘police officer’ client) …

So right here is an extremely important point - bright blue light in the evening can delay the timing of a person’s body clock - meaning that they fall asleep later.

And in case you missed the all important term in the above sentence, let me emphasise it …

Bright blue light.

In fact, you may have missed the most important word …

Bright.

The blue light needed to delay one’s body clock needs to be really bright. For example, the 1993 study above used bright white light (white light actually has all the colours from the rainbow in it - including blue light - more on that later).

The brightness of the white light was 2,500 lux. For comparison, when you go outside on a cloudy day, the brightness is roughly 20,000 lux. And it gets up to 100,000 lux on a sunny day.

For their 2001 study mentioned above, Leon and Helen used portable LED glasses with a brightness around ~950 lux.

Screen Brightness?

Because 97% of people using technology in the hour before bed, I’m going to guess you have too?

That means you’ve had various experiences - where some nights you have used a bright screen before bed, and other times you have not. Technically, you’ve been your own scientist who has been testing yourself. And you’ve likely come to some general conclusion about whether bright screens affect your sleep.

The thing about science is you need to measure things (ie, like how long it takes you to fall asleep). And you need to control a whole bunch of other things that can affect your ability to fall asleep (eg, your activity, posture, meal intake, caffeine intake, environmental lighting, temperature, sound, no bed partners or pets, how far the screen is in front of your face, and the brightness of the screen - to name a few).

Such controlled experiments can be best performed in a sleep laboratory. And that’s exactly what we did.

In 2014, we published one of the first studies to test the effect of bright screens on sleep.

The image above left shows a bright iPad, including the colours emitted from the screen - see that large blue spike? That large blue spike shows how much blue light comes from a screen. Yet the image on the right is when you use an app to filter the blue light - and it works because the blue spike is suppressed.

We were surprised with the results, as it did not match some of our experiences, nor what many people had claimed.

As we were to learn over the next few years - we were not alone.

Other people were finding that using a screen before bed did not mean you would take longer to fall asleep.

When we saw this happening - a penny dropped.

We used iPads - on the highest brightness - 40 cm away from teenagers’ faces - and only managed to get a reading of 80 lux.

So just to refresh your memory, when we perform Evening Bright Light Therapy, we use devices that are at least 500 lux.

iDevices are not bright enough.

The Blue Light from Screens?

As mentioned earlier, bright white light contains all the colours of the rainbow - indeed, screens from iDevices also emit all the colours of the rainbow. The colour they emit the most is blue (see the image from our study).

You can manipulate the amount of blue that is emitted from screens by the use of an app (eg, f.lux) or a setting on your device. This reduces the blue light, such that the screen looks a bit more of an orange colour.

This is exactly what we did in our 2014 study. We compared the bright screen, with using f.lux and a completely dim screens - but the time taken to fall asleep afterwards was ‘bugger all’ (Aussie slang for ‘nothing to write home about’).

Another way you can reduce the blue light being received by your eyes is to use tinted glasses. Colours like amber and orange reduce the amount of blue light that passes through the lens and into your eyes.

But let me just remind you of something.

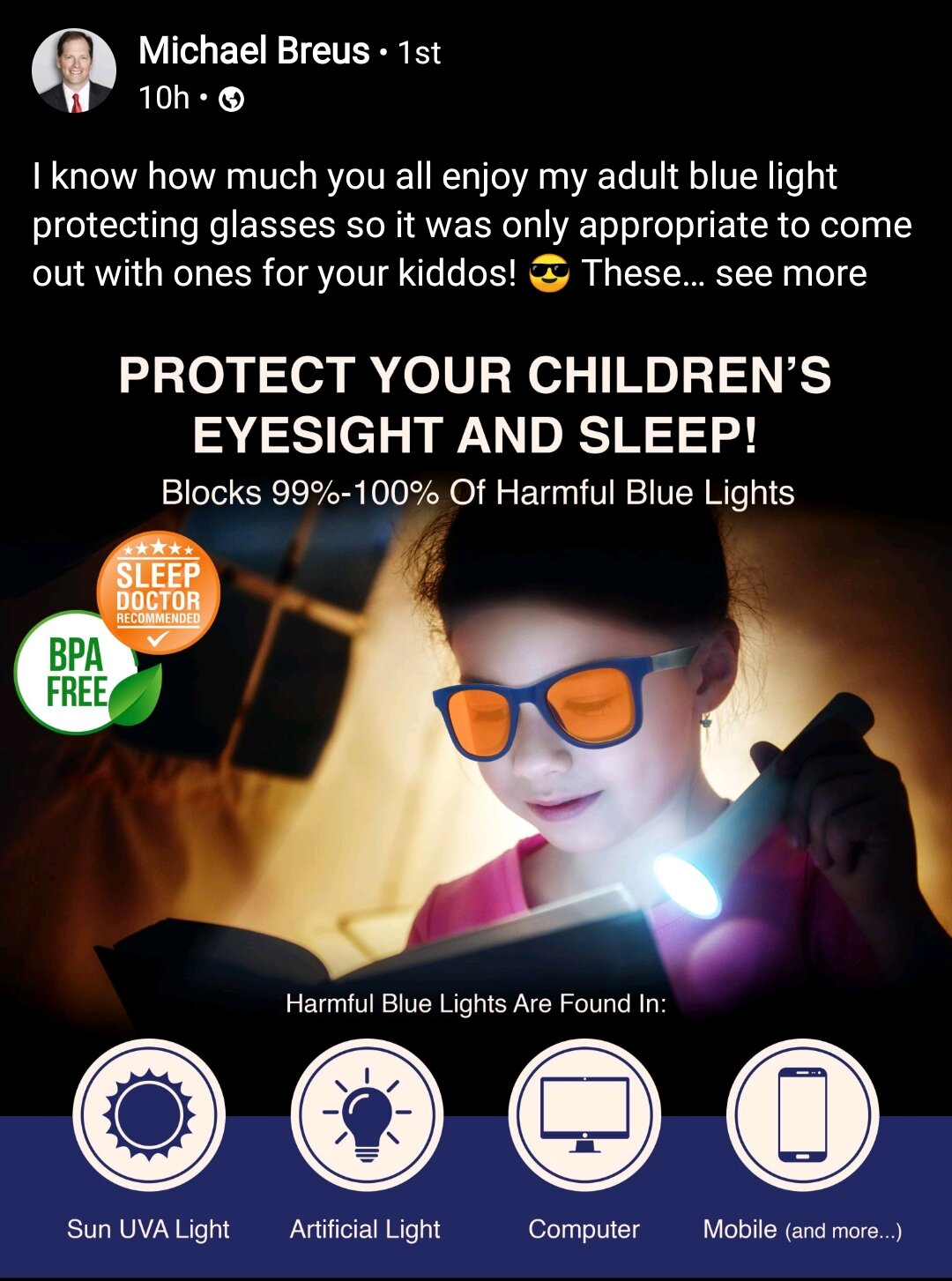

The light coming from screens is not bright enough.

So any person - retailer or even a ‘sleep expert’ - that is trying to convince you otherwise, has an ulterior motive …

Oops, I forgot to prove this to you.

Meta-Analysis of Suppressing Blue Screen Light

I recently saw in my social media feed a post about a new meta-analysis. If you haven’t heard about a meta-analysis before, it is a study that takes the data from all studies that have investigated a particular topic.

And this meta-analysis claimed that using screens with tinted-glasses before bed were effective at helping people sleep better.

This claim flew in the face of what I had learned.

So I couldn’t take this new claim at face value - I had to dig deeper.

Within this meta-analysis, the researchers report an effect on sleep duration. Now - if sleep duration decreases, there is one logical way that happens. And that is because people take longer to fall asleep when using a bright screen before bed.

So the best way to directly test this is to see the effect on the time taken to fall asleep between occasions when a bright screen is used, and on other occasions when the blue light from the screens is reduced (ie, wearing tinted glasses).

Yet, the researchers did not meta-analyse this data.

So below are the studies they reviewed - and the difference in the time taken to fall asleep. If the difference is a positive value, it means it took longer after using a bright screen. If the value is negative, it took longer to fall asleep after wearing the tinted glasses:

Ayaki et al. 2016 = +7.5 min

Knufinke et al. 2018 = +5 min

Ostrin et al. 2017 = -3.9 min

Van Der Lely et al. 2015 = -1.9 min

I think you get the picture, but if you simply average these values, it takes +3.8 min longer to fall asleep after using a bright screen.

But Wait - There’s More …

This meta-analysis chose studies on the following basis:

“The primary criterion to be eligible for inclusion in the current review was that the study administered the intervention aimed at reducing, blocking, or selectively filtering nocturnal blue-wavelength light exposure to the eye.” (page 2).

Hmm. Then why didn’t they include other studies? Like our 2014 one that used an app to reduce blue light.

So what I did was to add the following studies, that used an app or compared reading on a bright tablet or a printed book under dim light:

Heath et al. 2014 (our study) = -8.4 min

Chang et al. 2015 = +9.9 min

Gronli et al. (2017) = -8.1 min

If we add these studies to the meta-analysis, we get …

+1.34 min

This is so close to zero, that it means that the claim of blue screenlight causing us to take longer to fall asleep is not true.

But because the complete opposite is prevalent across the internet, it means this concept has turned into a sleep myth.

That’s right - we currently have one of the biggest sleep myths ever!

More so than ‘the best sleep is the sleep before midnight” and “REM sleep is a deep sleep”.

Conclusion?

Like our blog on ‘Sleep, Stress and Cortisol’ - if I’ve managed to convince you that ‘blue screenlight is a sleep myth’ then there’s a huge job to be done.

Getting people to think differently about this, will be like the Titanic trying to do a U-turn.

You’d need to share this blog amongst your networks, and ask your networks to share it.

Can you imagine how much attention you’d get by saying ‘Blue screenlight is the biggest Sleep Myth?’.

And if anyone ever challenged you, you can direct them to this blog.

So go ahead and share it - and if you want - let us know how you go.

Prof Michael Gradisar

Completion of this course provides you with the certified “BBT-I Practitioner” title and badge.

Price in US dollars